For almost a century, the United States Department of Agriculture has played a pivotal, albeit underappreciated, role in connecting this country with the trappings of modernity. It’s commitment to universal service began in 1936 with the passage of the Rural Electrification Act, which created the Rural Electrification Administration , a new deal agency charged with connecting rural communities and farms with electricity.

The REA was tremendously successful, growing rural electrification from 33% in 1940 to 96% in 1956. The REA was eventually incorporated into USDA, and in 1949 was given the added responsibility of rural telephony . Through its tried-tested-and-true model that involved the creation of local cooperatives and the championing of localities, REA connected rural communities at a staggering rate.

Don’t miss Christopher Ali’s “Ask Me Anything!” interview on Broadband.Money with T.J. York, which will take place on Friday, April 8, at 2:30 p.m. ET.

The successor of REA, the Rural Utilities Service, a division of USDA, continues the trend of rural connectivity through its broadband and telecommunications programs. Technology aside, the difference between then and now is that in contrast to its early starring role in rural electricity and telephony, it has taken a backseat when it comes to rural broadband policy and planning.

Most broadband planning and policymaking is done, for better or worse, at the Federal Communications Commission (and, with the passage of the Infrastructure Act, the Commerce Department’s National Telecommunications and Information Administration as well. But all of that seems to have changed with its October 2021 Notice of Funding Availability.

USDA’s significant changes to ReConnect

USDA has championed rural broadband deployment since the mid 1990s and continues to make crucial loans and grants through four different telecommunications programs totaling around $1.4 billion in investment. It’s most recent, and arguably most successful broadband program is ReConnect which began in 2018 with a $600 million congressional appropriation. Through the Infrastructure Act, ReConnect received another $2 billion. Thus far ReConnect has distributed $1.5 billion in loans and grants for rural broadband expansion.

It is ReConnect’s third, and most recent funding notice, where USDA flexed its broadband policymaking muscles. Here, USDA made three crucial policy adjustments to current standards presently set by the FCC.

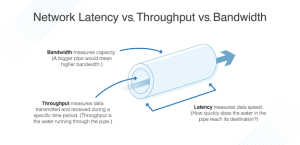

First, it defined an eligible area as any place lacking connectivity at 100 Mbps download/20 Mbps upload. This is a massive improvement from the FCC’s speed definition of broadband at 25/3 and thus dramatically increases the number of eligible communities.

Second, it requires networks that receive funding be able to meet or exceed speeds of 100 Mbps download/100 Mbps upload on day one. This, by definition, excludes previously ubiquitous technologies like DSL and geosynchronous satellite which have both proven incapable of delivering the speeds required by contemporary users.

Third, it prioritizes local governments, non-profits, cooperatives, and public-private partnerships. This differs from the FCC, which has traditionally privileged the largest incumbent providers, and differs from the Infrastructure Act which simply states that these entities cannot be discriminated against.

Single handedly USDA tried to reshape broadband policy, expanding eligibility, forcing grant and loan winners to upgrade their networks, and championing a local-first solution to the rural-urban digital divide.

New changes wrought by the Consolidated Appropriations Act of 2022

Unfortunately, this attempt may not last long. In the 2022 Consolidated Appropriations Act, passed on March 15, 2022, Congress reversed USDA’s ReConnect criteria in three crucial ways. First, it re-instated the 25 Megabit per second (Mbps) download x 3 Mbps upload threshold, rather than the 100 Mbps x 20 Mbps threshold previously proposed.

Second, it downgraded the 100 x 100 day-one requirement to 100 x 20. Even this is subject to a “to the extent possible” clause. Third, and as first reported by Kevin Taglang of the Benton institute for Broadband & Society, the Congressional explanatory statement that accompanied the Act chastised USDA for failing to act in a technologically neutral manner:

- The agreement is concerned that the most recent funding announcement dictates build out speeds that are not technology neutral and could inflate deployment and consumer access costs. Therefore, the Act sets the build out speeds to ensure that all broadband technologies have equal access to the program. In addition, the agreement encourages the Secretary to eliminate or revise the awarding of extra points under the ReConnect program to applicants from States without restrictions on broadband delivery by utilities service providers in order to ensure this criterion is not a determining factor for funding awards.

The Consolidated Appropriations Act, therefore is a mixed bag for USDA. While it provided an additional $436 million for the ReConnect program, Congress lowered the speed threshold, thereby reducing eligible communities and therefore permitted, once again, the deployment of technologies that cannot measure up to contemporary user needs and demands. Additionally, the last sentence in the excerpt above undercuts the localism impulse of USDA’s previous ReConnect announcement.

Words matter. Definitions matter. Technologies matter. As I recall in my new book on rural broadband Farm Fresh Broadband: The Politics of Rural Connectivity, technological neutrality is crucial to federal policymaking, but that does not mean that policy should be what the NRECA calls, “technologically blind.”

For what it’s worth, USDA’s ReConnect NOFA was indeed technologically neutral – it did not advocate for one technology over another, but rather set the speed thresholds at such a level that outdated technologies are ineligible. USDA should be applauded for its attempt to move the broadband needle forward to help local, rural communities. As we await the rulemaking proceedings of the NTIA for the $42.5 billion BEAD program, policymakers can learn valuable lessons from this federal department charged with championing rural communities.

Christopher Ali is Associate Professor at UVa’s Department of Media Studies and a Knight News Innovation Fellow with the Tow Center for Digital Journalism at Columbia University. He is the chair of the Communication Law and Policy Division of the International Communications Association and the author of two books on localism in media, “Media Localism: The Policies of Place” (University of Illinois Press, 2017) and “Local News in a Digital World.” This piece is exclusive to Broadband Breakfast.

Broadband Breakfast accepts commentary from informed observers of the broadband scene. Please send pieces to commentary@breakfast.media. The views expressed in Expert Opinion pieces do not necessarily reflect the views of Broadband Breakfast and Breakfast Media LLC.

![Read more about the article What is Dropbox? [A Full 2023 Cloud Storage Explanation]](https://sonicsurfisp.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/01/what-is-dropbox-a-full-2023-cloud-storage-explanation-300x180.png)