WASHINGTON, November 9, 2023 – In the months before President Joe Biden signed into law the historic infrastructure law on November 15, 2021, Republicans and Democrats wrangled over how much to spend on broadband.

Democratic lawmakers sought $100 billion, while their Republican counterparts countered with $65 billion, saying the former’s proposal was wasteful and excessive. The final score was $65 billion, with $42.5 billion of that earmarked for infrastructure in the Broadband Equity, Access and Deployment program, or BEAD.

Crucially, the BEAD program adopted a new definition of what adequate broadband would look like: 100 Megabits per second download and 20 Megabits per second upload.

It turns out, that speed threshold is serving as a key reason why money from BEAD and other programs will be used to cover already-subsidized projects under an older Federal Communications Commission program that has only recently completed some broadband builds using older technology.

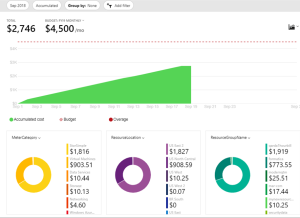

Broadband Breakfast has analyzed the data and spoke with experts and former FCC officials about the pitfalls and problems with the Connect America Fund Phase II, or CAF II, a $10 billion funding program that started in 2014.

FCC officials working on the program said they knew the 10 Mbps download and 1 Mbps requirement was low and would lead to further subsidization down the road.

But they went ahead with it because they needed a political win after the low adoption of the program’s predecessor: Connect America Fund I.

Right after the program started, the FCC changed broadband speed requirements

The problems started just six weeks after the CAF II program was finalized, when the FCC in 2015 approved a new definition of adequate broadband: an internet connection of at least 25 Mbps download and 3 Mbps download.

Critically, it didn’t migrate the CAF II threshold over to the new definition out of fear it would disincentivize interest in the program.

“In retrospect I can say it was a mistake having 10 * 1 Mbps be the standard for CAF Phase II,” said Carol Mattey, a former FCC bureau chief who worked on the plan.

The program offered large telecommunications companies, called price cap carriers, annual funding in exchange for providing that 10 * 1 Mbps service to rural areas across the U.S. without access to faster connections.

The FCC was desperate for providers to get on the program. It realized that it had many more years to formulate a reverse auction process, which would be used under the program’s successor, the Rural Digital Opportunity Fund, and so it was trying to entice providers to accept money by keeping the speed threshold low.

‘It was scandalous… it was graft’

Instead of waiting to formulate the reverse auction, which involves the providers bidding for the lowest amount of public dollars, they wanted to show that they were committed to connectivity – even when they knew that the speeds were low.

“It was scandalous, what the commission did,” said Jonathan Chambers, the FCC’s policy head during CAF II’s implementation. “It was graft.”

Chambers said he and the economists in his office were opposed to subsidizing price cap carriers at 10 * 1 Mbps from the beginning. He saw it as a giveaway to a powerful industry with too few strings attached.

In 2012 and 2013, the FCC offered price gap carriers a baseline of $750 per location to expand internet at the then-minimum broadband speed of 4 * 1 Mbps under CAF I. Five companies, including AT&T, Lumen, and Frontier, accepted a total of $225 million.

That didn’t feel like much to agency staffers who spent years updating the High-Cost Fund, which had provided companies subsidies with much fewer obligations than CAF I.

“Basically nobody took it,” Mattey said. “At the time, it felt like a failure. We’d gone through all this trouble to reform universal service and nobody wanted the money.”

All that amounted to a situation in which FCC staff felt they needed a success after the lackluster CAF I, according to Mattey. With a competitive bidding procedure known as a “reverse auction” still years away, that meant getting big telecom companies to work with the agency on another round of funding.

Those companies had already pushed back on raising the minimum speed from 4 * 1 Mbps to 10 * 1 Mbps, and setting an even higher benchmark would have risked another round of refused money.

“There was a desire to make this a success,” she said. “Better to take an incremental success than to be bold and have an absolute failure.”

CAF II and CAF I were always intended to be a stepping stone, she said. It would serve as a stopgap measure to get people connected while the agency worked out the process for an auction, in which companies would compete for subsidies with plans for building and maintaining new infrastructure.

But the FCC had never administered a reverse auction for broadband subsidies before, and creating one took time. The CAF II auction, in which areas the price cap carriers turned down were put up for auction, took a total of seven years to put together and was not ready until 2018.

Carol Mattey

Even FCC Chairman Tom Wheeler felt the pressure

Tom Wheeler, the FCC chairman at the time, declined to talk about the negotiations among commissioners and telecom companies. But he told Broadband Breakfast he felt the pressure Mattey described.

He confirmed that the 10 * 1 Mbps benchmark was set as low as it was out of fear the price cap carriers would refuse the money if it meant a more substantial upgrade.

The low benchmark worked. Ten companies accepted a total of more than $1.5 billion each year for the next six years in exchange for getting 10 * 1 Mbps service to more than 3.6 million homes and businesses. They would ultimately build to slightly more locations and get a seventh year of funding at the same amount, for a total of more than $10 billion.

But the tradeoff was ultimately not worth it for Mattey. Upping the standard to 25 * 3 Mbps and letting areas turned down by price cap carriers go to auction would have served them better than funding such low speeds, she said.

Michael O’Rielly, a commissioner at the time, concurred with CAF II’s adoption. He said in public statements at the time that he had reservations about the program’s speed benchmark. But he told Broadband Breakfast that in hindsight he feels the low speeds were better than nothing for unserved areas.

“I’ve seen those that have nothing and can’t get connected,” he said. “If you can give them 10 * 1 they can actually do something with it, even if it’s not everything you can do with 100 * 20.”

Michael O’Rielly

93 percent of locations received service of only 10 Mbps * 1 Mbps

The three biggest winners at the time were Lumen, AT&T, and Frontier Communications. Lumen led the pack with a $514 million annual award, while AT&T and Frontier were given $428 million and $283 million, respectively. Windstream received almost $200 million.

The price cap carriers were supposed to get money each year until 2020, when they were required to have finished deploying upgraded infrastructure in their respective areas. Citing pandemic supply chain issues, they took another year. That meant builds finished as late as 2021 were providing 10 * 1 Mbps service – a technological standard deemed by BEAD to be obsolete.

Companies followed the minimum standard set out in the program. FCC data, reported to the agency by those companies, show more than 93 percent of all locations served with CAF II infrastructure received only 10 * 1 Mbps service.

And that took place after the commission had declared 10 * 1 Mbps as substandard. That 93 percent of locations represents about 3.7 million homes and businesses across the country that are now limited to no more than 10 * 1 Mbps internet service.

Most of those, more than 2.9 million, did not receive service on their internet connections until 2019 or later.

That 10 * 1 Mbps threshold was too low for the program to meaningfully connect people, said former FCC Commissioner Jonathan Adelstein. He left the commission in 2009 to head the Department of Agriculture’s Rural Utility Service, an infrastructure funding agency that supports broadband deployment.

“Well, 10 * 1 was our standard in 2010,” he said. “For people to be building that in 2020 is really inadequate.”

New money being spent to cover the failings of old money

Some of those have already been targeted with more federal money. In 2020, the FCC put areas with internet below 25 * 3 Mbps, including those served by CAF II recipients, up for a reverse auction process, the Rural Digital Opportunity Fund. Under RDOF, companies competed for subsidies with plans to cost-effectively build and maintain new infrastructure.

Winners have been allocated more than $6 billion to build and operate networks over the next 10 years under the RDOF program, according to the FCC, with another $14 billion still earmarked for the program. The minimum speed threshold for the auction was 25 * 3 Mbps, but the fiber being deployed by winners almost always provides speeds far in excess of that.

As part of RDOF, the price cap carriers lost 1.2 million homes and businesses to outside bidders, about a third of their previously subsidized locations. Competitors demonstrated to the FCC they would be able to get better internet for less money to the same areas price caps had been receiving money to serve.

Almost every single winning bidder committed to deploy fiber-optic cable: The fastest, most future-proof technology available.

Lumen, the biggest CAF II recipient, lost more than 250,000 locations through the RDOF process. It beat out competitors for just 19,000 locations.

Frontier lost another 285,000 homes and businesses, beating competitors in more than 10,000.

AT&T lost more than half a million locations in the RDOF auction, winning zero locations.

Those losses came largely at the hands of smaller companies and local cooperatives. Charter, the major cable company, also scooped up locations across the county.

Jonathan Chambers

Is there a silver lining?

CAF II did make some positive changes to broadband subsidies generally, Mattey said. There were no requirements at all for funding recipients before the program, which instituted speed minimums and reporting requirements.

Mattey and others also drew up a process for determining exactly where subsidized companies were operating, which again did not exist before. And then there was the smaller CAF II Auction, which happened in the areas where price cap carriers turned down CAF II funding.

The auction happened in 2018 and got faster service for less money. A total of 100 bidders won $1.49 billion over 10 years to serve more than 700,000 locations. The minimum required speed was still 10 * 1 Mbps, but more than half the winning bidders committed to serve customers with 100 Mbps download, and more than 99 percent committed to 25 * 3 Mbps.

BEAD, the latest round of broadband subsidy, requires minimum speeds of 100 * 20 Mbps and prioritizes fiber. Areas receiving less than 25 * 3 Mbps are designated “unserved” and given special priority for funding. States are not allowed to allocate BEAD money elsewhere until all unserved areas are set to be provided with high-capacity broadband.

FCC data still shows more than 800,000 CAF II-funded locations still have no reliable, fast internet infrastructure nearby, and are not among the 1.2 million with RDOF commitments. That puts them at the front of the line for BEAD funds. It’s not clear whether the remaining 1.6 million homes and business in the proximity of faster technology are themselves being served with that speed, meaning they may well also be slated for more federal funds.

“RDOF and BEAD are wholly replacing these networks,” Chambers said. “The FCC spent more than $10 billion, and what did we get for it? Nothing.”